Dating apps like Hinge and Match, let you choose your dating preferences. For example, you can say that drinking and smoking weed, in a potential match, is a “deal breaker.” However, if you DO choose this option (which I have) your pickings dwindle down to roughly one-sixteenth. You think I’m joking but I’m not. Combing the dating circuit for a guy who doesn’t drink or smoke weed within a 50-mile radius of Kansas City is like fishing for a tri-colored sea horse in a bass pond. An anomaly. That rarely doth exist.

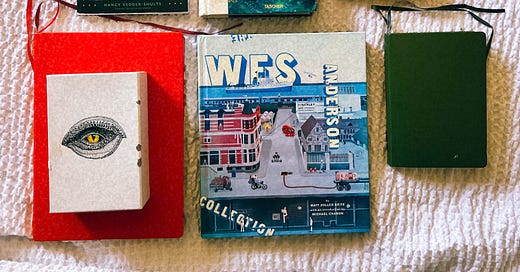

This obscenely disappointing discovery led me to widen my search criteria to circumscribe, rightly or wrongly, the ages of 29-44. The first guy I dated was 29. On our third date I somehow convinced him to watch “The Royal Tenenbaums.” (Another of my more obscure preferences includes MUST BE OBSESSED WITH WES ANDERSON). Just so they know what they’re in for.

I hadn’t watched “Royal Tenenbaums” since it first hit theaters in December of 2001. I had been away at college for 3 months and already collected a Freshman 10. My brother and a bunch of his friends and I caravanned an hour east to Lafayette, the next biggest town over, where the movie was showing.

I don’t remember the details only that alcohol was involved, likely in all of it. I do remember the crisp Christmas feel of the soundtrack. The fresh burst of honesty in each symmetrical 70s snapshot. I loved that Margot smoked in the bathtub with the fan on, and that Luke Wilson’s character had a pet hawk named Mordecai that sometimes wore a helmet. And the scene where Richie slits his wrists with a razor blade to Elliot Smith’s “Needle In The Hay” elicited the same strand of tears back then as it did this time around.

But the thing that caught me most off guard sitting on a 29 year olds apartment couch with his dog named Mila, was how Anderson captured the understated beauty of the atypical family. The split parents. The dysfunctional, obsessive-compulsive, manic depressive, drug-addled twenty-something kids. The lack of boundaries. The absence of communication. The pain of being alive and feeling it all. Yet in the brokenness, and, one might argue, because of it, Anderson manages a rare ingenuity that issues magnificence to mayhem. Gathers his audience back to the Big Picture through a series of oddly balanced relationships. Object, animal, typeface, dialogue. And out of the obscurity of the unlikely is birthed another kind of beauty. The real raw, shifty kind. The kind that moves you to exhale emotion you didn’t know you had bottled up in the kettle of your heart. I left that night knowing I probably wouldn’t see the manchild again. But knowing that my family, in all its messy exquisite beauty, would be alright.